Respecting Our Life: The Legacy of C.G. Jung

by Linda Missouri, LMFT, Former Club President

Each of us has an inner psyche that creates healing symbols just as a plant creates blossoms. These symbols, used well, can be our great guide, friend and adviser.

This discovery was one of many made by Carl Gustav Jung, one of the great doctors and innovative thinkers of the 20th Century. Born July 26, 1875, in Switzerland, Jung began his autobiography Memories, Dreams, Reflections in 1956. He finished Man and His Symbols just weeks before he died in 1961 at age 86.

We can pay attention to the symbols from our dreams, from our fleeting thoughts and fantasies and from the negative or positive projections we readily cast onto other people and other nations. When our conscious mind and unconscious psyche learn to live at peace and to complement one another, we become more calm, relaxed, whole and integrated. This balance, growth and integration process that Jung called individuation takes a lifetime.

C. G. Jung dedicated himself to observing his own inner world. He found insights in the study of medieval alchemical texts and working with patients’ dream symbols. In his travels to New Mexico and parts of Africa and India, he gained a multi-cultural perspective. He developed an empirical yet radical approach to the human personality. His approach, known as analytical psychology, embraces the opposites, the feminine, and the spiritual. Jung and his early mentor, Sigmund Freud, parted ways when Freud could not value Jung’s differing ideas.

Jung affirmed the mind-body connection. He wrote, “The psyche and body are not separate entities, but one and the same life.” When we ignore either, symptoms develop. Discovering the deeper meaning in our symptoms is vital so we can correct our course.

In a low period of his life, Jung began a self-experiment. He transcribed his inner experiences in words and illustrations in The Red Book. One image from his imagination was an old man named Philemon. Jung and Philemon had long helpful conversations with Philemon having a superior insight, like a wise teacher. This process of dialog became known as active imagination.

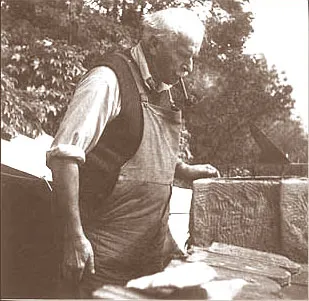

To balance his intellectual pursuits, Jung learned masonry while building two towers in forested land on Lake Zurich. In the privacy of his land and towers, Jung used stone carving, gardening, creative journal writing, solitude, and even cooking for his own self-healing. He encouraged his patients to discover and use their own creative outlets.

The second half of life and growing older were of primary interest to Jung. He said the afternoon of our life cannot be lived by the morning’s rhythm. He demonstrated that one can move toward the end of life with a new vitality, finding the real meaning of one’s unique journey. A crucial question he posed was “Are you related to something infinite or not?”

Jung said, “There is no birth of consciousness without pain.” With courage and with a regular inward turning, we can dare to look at our own symbolic life and our ego-frustrations, losses, fears and shadowy shortcomings. Gradually, we can accept our human condition as part of our total personality. This work of self-acceptance releases life-transforming energies.